Ravi and I lived in Mogadiscio for two years in the 1960s when Somalis were in transition from Italian and British colonials to independence. Ravi read and spoke Italian and I picked up enough for shopping and to follow conversations. (Somali is difficult and one could get by with Italian.) Ravi was doing research on the governmental system and I involved myself in the casbah communities. Our social life otherwise consisted of long discussions in the evenings over drinks with Somalis who spoke either Italian or English, and in the afternoons over tea in our compound garden, in English, with men from the local Indian community who stopped by when “rounding” after the siesta.

Ravi watched, listened, observed and said to me, “These people know one another, they have grown up together, and they will be together all their lives.” I thought the remark a bit odd, which is why I remember it. I wondered why he mentioned something so obvious and ordinary but noted that he thought it important.

Now I understand, at long last. He was telling me that these were people from communities in which family and social networks were stable and he recognized the way they talked and behaved with one another. It reminded him of home. He had wonderful parents and brothers and sisters, his mother’s large family of talented and generous individuals, cousins from Papaji’s family, school mates and buddies in Bombay. He had no reason to ever leave them and fully intended to return home after his Fulbright scholarship expired. These were the people he knew, had grown up with, expected to be with all his life.

From the family I met I could understand Ravi’s attachment to them. One of his aunts from Bangalore, known to everyone as Baby, came as a graduate student to our university, chosen because Ravi was there. She was Didai’s, his mother’s, youngest sister, only two years older than Ravi, living with Dada, the brother who kept the family home and business. Ravi had been writing to Dada as well as to Papaji. I met Baby on the first date I have with Ravi and saw her regularly after that. I liked her; she was very attractive and easy to be with. This was in June 1953. Our marriage by a Justice of the Peace in the city courthouse must have looked terribly spare to her. (a snapshot of us is here) At the small celebration our graduate student friends held for us in the afternoon she wrapped a sari over my dress. I supposed she wanted something to be Indian and that was fine with me. That summer Dada in Bangalore wrote in a letter to Papaji in Benares, “… Baby wrote to say that Ravi was getting on fine and that his wife is an accomplished girl. Personally I feel happy and proud that he had the courage to decide this serious and important matter of life all by himself. …” Ravi’s marriage was the first in the family not arranged by the family.

A year later, in June 1954, Ravi sailed to India, as required and paid for by his Fulbright scholarship, and soon discovered that finding a job in India would be extremely difficult. A young man had to be set up in a career through connections, a complex and chancy process, and I heard later from Indians who returned home that having studied abroad was often a negative with employers and colleagues. Papaji could not help. His own career had fallen apart and the family was in bad financial straits. In the midst of this, Ravi received my letter informing him that I was in the hospital with a broken leg. I could not send telegraphs, only letters. He wrote me that he would return immediately, by air. And how were we to pay for this? Before my hospitalization I had been waitressing in a restaurant, earning money for Ravi’s return by ship. We had no savings; I had no back-up with anyone and no idea whatsoever about how to borrow money. Papaji could afford neither the plane ticket nor going into debt for it, but Didai found a way. We were rescued by a loan from within the extended family, made available to Ravi in a fashion I have described elsewhere.

Ravi returned to the campus and to me. His professors arranged for him to teach a course in two university extension colleges in towns nearby. An older couple who had befriended us engaged a lawyer to sue the drunk who hit me and they helped us borrow money to live on. We paid off the India debt within a year. The insurance company settlement covered our other debts with just enough extra to buy a typewriter. Nothing more. The following year we both were back in graduate school, living on our Teaching Assistant incomes, tutoring and grading papers. I escaped needing surgery and the leg was normal until I was in my fifties, when arthritis set in at the knee.

In the spring of 1955 Ravi and I prepared ourselves for him to spend the summer in New York City. A high level official in the Indian Embassy in Washington had been on campus. He was touring universities in the U.S. on a survey of Indian students in America. There were not many, only two others on our campus, so the official had plenty of time to talk with Ravi, was most impressed by his qualifications and seemed eager to help him. Ravi had decided that diplomacy and the foreign service would be his future. In a 1952 letter from Papaji to Dada, “Ravi secured marks over 90% … and 100% in his favorite subject, South American History and political situation. He has polished his Spanish, too. He is determined to be an ambassador in some South American republic …” The Indian official encouraged Ravi and promised to secure for him a prized United Nations summer internship. It would be the beginning of his career. Then it happened one day that a new Indian girl on campus, evidently from a wealthy family and certainly not a serious student, breezed into our apartment to tell us she would be away for a while. She talked about the fun she would have that summer in New York, after she visited her family in Washington. She barely bothered to mention that her New York stay and all the shopping she planned to do would be paid for by her internship at the U.N. Thus ended Ravi’s dream.

In 1965 in Mogadiscio, Ravi’s observation about people living a stable, traditional life, was made at a point in his life when he had American citizenship, was a professor in an American university, had two American children and an adopted Indian boy, had brought two brothers into our home for them to attend university, helped a third come to study in the States, had another living in a city near us with his Indian wife and their baby, and had held his sister’s Indian wedding in his American home. Psychologically, Ravi was somewhere between traditional relationships and the fluid world where, as he told me, everyone is a stranger. I had grown up a stranger, so could compare only intellectually and not, as he must have, with conflicted and uncertain feelings. No need to point out to Ravi that he was doing quite well as a stranger in America after finding no job, let alone a career, in India and that his family was benefiting from his success.

After much exploring into Ravi’s life before he set out for America, I have concluded that although he lived most of his childhood in Benares his roots were in Bangalore with Didai’s family. The brief time he spent in Bangalore and the city itself played an outsized role in shaping his personality and character. Despite the tradition in India of a woman leaving her own family at marriage, Didai remained close to her parents and brothers and sisters. From Papaji’s letter collection: Two letters are from Didai to Panditji, her father, and she longs to see him. Papaji wrote regularly to Panditji and in a number of the letters he informs Panditji how Didai misses them all but is too busy with the children for composing letters. In one letter, Didai adds at the bottom of the page that she is busy and “… engrossed with these babies & their illnesses … Virendra is teething so he is very troublesome …” and “… if you don’t write to me I feel very unhappy … ” She continues up the right margin of the page naming everyone by nickname, – Ma, Badi Ma, Munni, Munnu, Bachhu and Bachhi — and she sends her love, with respectful pranams, and finishes in the top margin with an explanation about photographs not sent because they did not turn out well.

Panditji and Papaji wrote to one another as if they had been long-time friends, so the father- and son-in-law tie was doubly strong, especially given that Papaji had broken from his own family. In 1933, Papaji closed his office in Karachi and he and Didai went to Bangalore with babies Ravi and Agit to stay with her parents. From there Papaji proceeded to Benares, where he would become Manager of an insurance firm, and having accommodations ready for them, wrote to Didai to bring the children and belongings to their new home. In the following years, letters indicate that Didai’s brothers and sisters were writing to her, and in his tours for work Papaji arranged to visit her brothers in their colleges and send word to their father about what he saw. One brother was feeling lonely and did not like the European food he had to eat.

In 1939, when Ravi was eight, Didai, the six children and their servant boy Ramsingh spent several months in Bangalore. Panditji had had a stroke and she, as eldest daughter, Didi, was there to help care for him until he passed away. By that time, Panditji, Ma, Badi Ma, two younger sisters, and one or two of the younger brothers were living in a large house behind an even larger house in which Panditji had located his printing press. The houses were on Ulsoor Road in a compound surrounded by a low wall. The larger house turned business workplace, facing the road, had originally been a 19th century mansion, possibly the summer residence of an English businessman. I found a reference to it in a book published in London in 1875.

Ajit remembers a large dog he had been warned not to befriend because its sole purpose was to chase away cows that wandered into the compound, which it did with loud barking and frantic running about. When I asked Ajit if he walked along the road he said he went past houses where English people lived and sometimes saw them working in the garden. They always had a sign on the gate: Beware of Dog. Scary English bulldogs. The houses he and Ravi saw were substantial. The British lived well, and why not? Labor was cheap, even that of workmen skilled in the building of palaces, and construction materials were plenty. (Ravi and I saw similar colonial privilege in Nairobi before it disappeared.) See photos of bungalows in Bangalore Part Two. I think the modern bungalow shown, if it were set on a two acre lot and surrounded by a low wall, would be similar in grandeur, if not exactly in style, to those the 1930s.

In Benares Ram Singh took the boys to school on a bicycle and in Bangalore did the same. I am fairly certain their school was Bishop Cotton Boys School. From Ulsoor Road, turn left onto Dickenson, cross South Parade (MG Road), proceed down Residency Road, turn right onto St. Marks Road, and voila, the school.

I assume, having no information on the family home and ordinary household shopping, that Ma and Dada’s wife, assisted by servants, would have bought food and everyday goods from the Shivajinagar marketplace, especially in Russel Market, the grand bazaar.

The Indians in the cantonment were predominantly from Tamil Nadu and would have spoken Tamil and English. Ravi’s grandmother and aunts spoke Kannada, Bengali, Hindi, Marathi, and English. English had to be the language both in the home and in public life.

The printing press and the family house were in the Cantonment and this is where Ravi lived again, this time for a year, from the summer of 1941, when he was ten and a half, into the summer of 1942. By then, Dada was head of household. At Panditji’s death, he had given up a career in electronics and returned home to manage the press, take care of his mother and sisters and become the center of the family. Hence, when Ravi came down with stomach problems, was not recovering well, and Papaji was worried as always about the Benares climate and his children’s health, Dada suggested the boy be brought to Bangalore. Papaji did so, of course, most likely with considerable pressure from Didai.

Papaji wrote that he had gone to Ravi’s Benares Convent School and asked the Rev. Mother for a School Leaving Certificate to present to the school in Bangalore. His teachers and she told Papaji they were sorry to lose Ravi. “He is one of our cleverest and best-behaved pupils.” Even before I had met Ravi I heard a professor talk about this outstanding student from India. Ravi grasped ideas quickly and presented them in a way that was interesting and easily comprehended. And there was his command of the facts. Once, in a meeting where he was speaking about oil companies and colonialism, he amazed us all with the details he presented, especially with the numbers he cited to prove his point. I noticed that at times he stared into space rather than look at us. He told me later he was looking at the back wall of the room that so he could see his term paper notecards projected there from memory and read the numbers he had written on them.

Ravi’s photo of St. Joseph’s

Ravi attended St. Joseph’s Collège on Residency Road. He once mentioned a teacher from England who had given him special attention. I think it extraordinary that Ravi was tutored in French while in Bangalore. The family spared no expense in schooling for their children. He must have asked for the lessons because I know of no one else in the family with the slightest interest in France. St. Joseph’s in 1941 was under a new management. The school had been founded in 1882 by the Paris based Fathers of the French Foreign Mission and turned over to the Jesuits in 1937. French was probably still being offered and Ravi would have picked up on that. He loved learning languages and never shied away from learning and using a new language whenever he had the opportunity. Our very first conversation happened at a party when I overheard him comment about me in Spanish to his buddy. I turned around and corrected his Spanish. He liked that. While we lived in Ankara he took French in the local Alliance Française and spent a summer in the south of France in a special language program. In 1975, he arrived at his job in Paris fluent in French.

To go to St. Joseph’s, Ravi would have walked along Ulsoor Road, turned left on Dickenson Road, crossed South Parade (MG Road) to Residency Road. His school was not far, on his right. He would have passed the Mayo Building. See Comments, October 14 and 25 on this interesting building.

Mayo Building 1940 from Residency road

Further down Residency Road was The Club.

Bangalore Club

After considering the alternatives, I think this is the family’s Club. Horse racing interested Dada; he and his friends talked about the Race Course. When visiting in Bangalore, after walking along the streets of an Indian city, among the children, I did not want to hear men discussing how to best care for a prize race horse.

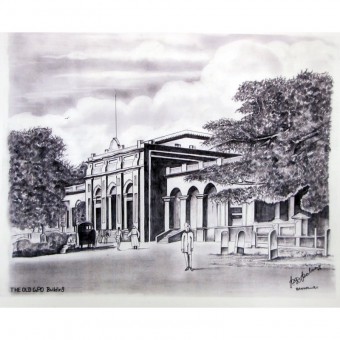

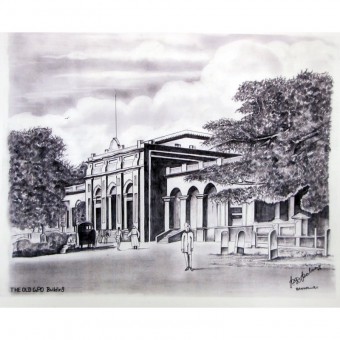

Everything the eleven year old Ravi saw about him was British in style and different from his surroundings in Benares. He would have walked to the Post Office in Cubbon Park to look for letters and mail his letters home. I wonder if Dada had a box there. In Mogadiscio that is how one received mail.

The Museum, below, is still on Post Office Road. It houses a major library and is a handsome building. I like to think that Ravi was curious and wandered through it.

He would have played in the park and undoubtedly been impressed by the Attara Kacheri, the present High Court of the State of Karnataka, shown on the map above of Cubbon Park. Pictures of this and other buildings in the cantonment are in the previous essay on Bangalore.

Walking to the park, down MG Road past British shops, he would have seen impressive church buildings, St Marks Cathedral, the oldest church in Bangalore,

and the Wesleyan Church.

Perhaps on his way home he went as far as Trinity Church to explore the sights.

As a child in Bangalore, Ravi lived in a world visually British and European and a home culturally Indian. Benares had a cantonment and his European school, St. Mary’s, was in it, but nothing could compare with Bangalore. Bangalore is the place he talked about with me, took me first to see.

In October, 1947, Papaji wrote to Dada, “… Ravi is going to have holidays for a fortnight and wishes to spend it in Bangalore … He had his tonsils removed last month … was not fully recovered… and had to apply himself for his terminal examinations. … a change may do him good. Besides, perhaps he told you , he wants to go for journalism and hopes to sit in the magazine publishing office to see how the work is carried on there. …” A telegram from Dada was received a week later: “Send Ravi Immediately” I cannot know if Ravi went to Bangalore; there are no letters after this until June 1950. He may have gone for a visit and returned to Bombay in time to continue his studies at Wilson College.

In August 1942 I turned twelve. Where was I while Ravi in Bangalore attended one of the best schools in his country, lived with a loving, prosperous, socially prominent family in a large house well staffed with servants, walked among fabulous historic buildings and played in a very special park? I honestly do not know exactly where I was. My father, an unskilled worker and often unemployed, placed me with various working-class families in small towns in eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania. They were not my family and they did not love me, but they were not cruel, either. I did not know my mother. It was the Great Depression and she could not keep me; I was five when Dad came and took me away. I knew where Mother lived and at sixteen took a long train trip to meet her. Unfortunately, she and I had little in common but her small apartment was four blocks from Wisconsin’s marvelous state university on a beautiful campus, the first I had seen, and I fell in love with it. At seventeen I returned to live with her and finish high school there, thus qualifying to pay the university’s low tuition for in-state students. While still seventeen, I moved out on my own. I had already been working for years in stores and as a waitress; I could support myself. Unlike Ravi, I did not grow up privileged, but each town I lived in had a public school with books and proper teachers committed to their profession. I loved them and the public library and the librarians. I grew up poor in a society with government that invested in institutions serving all the community’s children (although Black communities far less well). The public infrastructure — schools, libraries, safe water to drink, safe food, safe streets, city buses and passenger trains — made it possible for me to achieve the life I wanted.

Grandmother and Me

I add the note about Grandmother not being my biological kin because the fact is important in defining the person I became. Teachers and church women, and especially Grandmother, were good to me. She loved me when I was a child and she was the person with whom I could talk, whom I most respected. My father left her without so much as a thank you for having raised him, yet she was always loving towards me. In her last year of life I was the one person she remembered. She told the nurses that I was her friend. In the photo she is holding me, almost in tears, because I had just told her I was pregnant. Her baby was about to have a baby. Ravi must have taken the photo. He came from a strange and foreign land but she accepted him as long as he was good to me.

Such were the differences between Ravi’s childhood and mine. No wonder it has taken me time to learn and understand his.

Next – more about Ravi and me in Bangalore.

Read Full Post »

He wrote:“Grinding wheat at home — before a commercial grinding mill was opened near our home — was not necessarily considered a menial job. I can clearly picture my grandmother (this is going back more that 70 years) and her daughter (my aunt) sitting across from each other and slowly grinding the wheat and having a deep intimate conversation. It was an occasion for women to socialize.

He wrote:“Grinding wheat at home — before a commercial grinding mill was opened near our home — was not necessarily considered a menial job. I can clearly picture my grandmother (this is going back more that 70 years) and her daughter (my aunt) sitting across from each other and slowly grinding the wheat and having a deep intimate conversation. It was an occasion for women to socialize.

You must be logged in to post a comment.